Give me liberty, or give me Afrofuturism: Frank Miller’s dystopian America

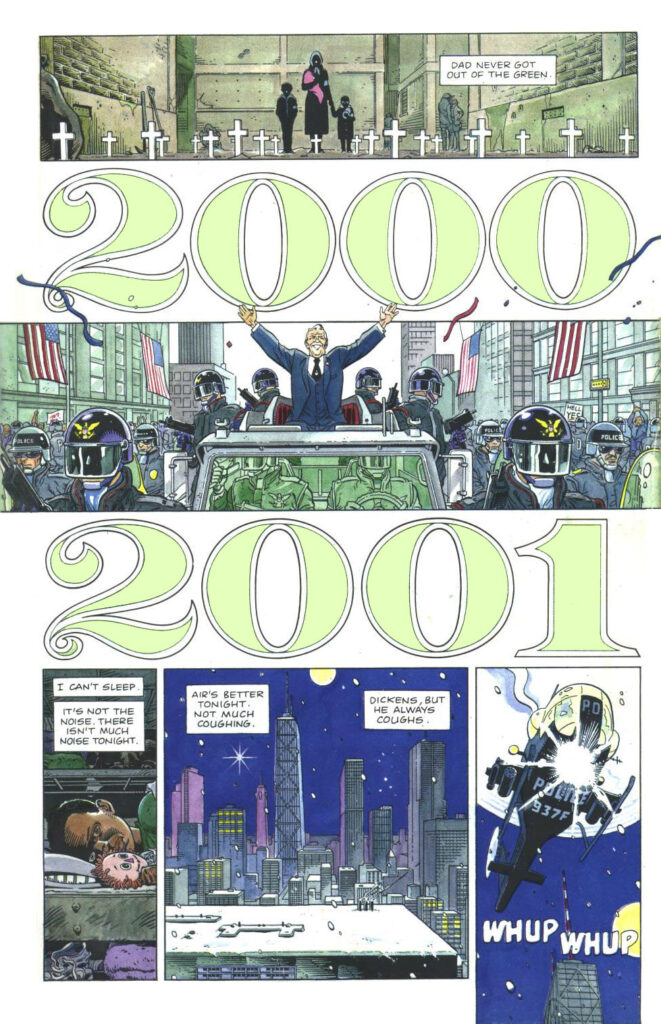

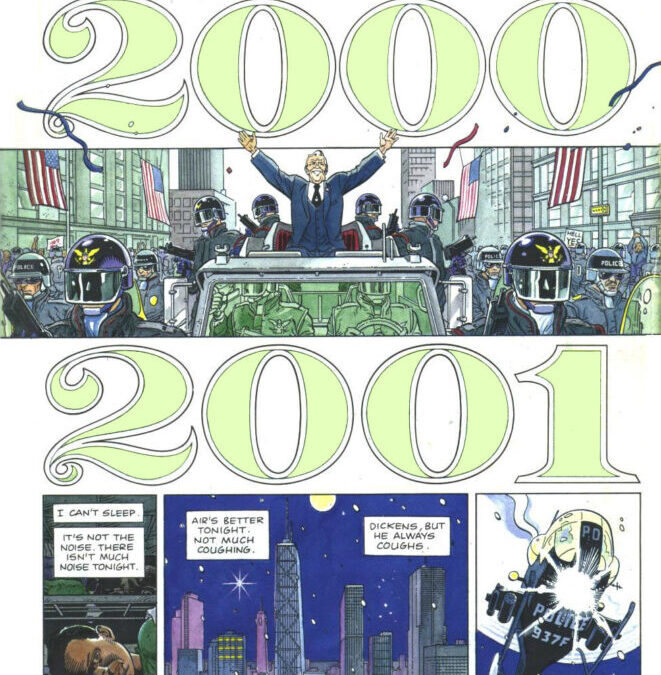

A short-lived but popular collaboration between Frank Miller and Dave Gibbon titled Give me liberty raises the question of what Afrofuturism is. The four-part miniseries depicts the epic life of Martha Washington, a Black girl from the infamous Cabrini-Green public housing project in Chicago. She is born just as fictional president Erwin Rexall wins his first term in 1996. The series saw publication during the presidency of George H. W. Bush (1989-1993), a rare occasion when one of the USA’s two parties managed to win a third term. Indeed, the post-Reagan America that was emerging triumphant from a decade of neoliberalism and following the collapse of the Soviet Union had an incumbent flavor. In the story, Rexall repeals the 22nd amendment that blocks re-election and then keeps winning them. But his victories come at a steep cost for the nation: every inaugural parade features an increasingly repressive cadre of security forces surrounding the presidential motorcade.

Life in Cabrini-Green is a microcosm of the American carceral state for Blacks that was enhanced during the Reagan years. The housing project is more of a jail than a home, with apartments that resemble prison cells and sleeping rooms filled with bunk beds. These conditions are no stranger to the immigrant families currently being detained at the border with Mexico either in the Trump or Biden administrations. After the police murder her father during a protest over harsh conditions at the housing project, and her self-defense killing of a bully who assassinated the only teacher who recognized her talents and tried to help her, Martha is institutionalized. But budget cuts enacted by President Rexall’s neoliberal policies close the hospital, and Martha is left homeless.

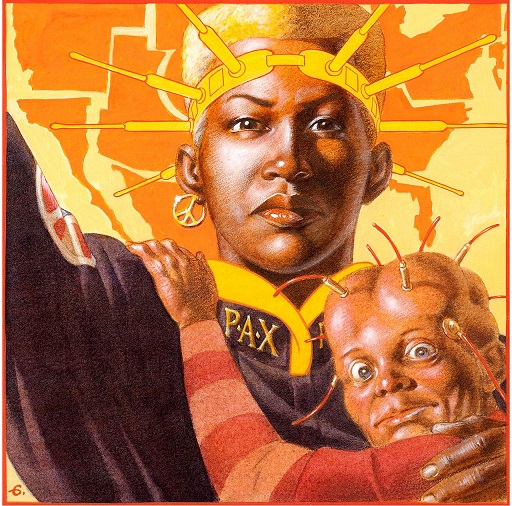

Mirroring the actual USA, the act of joining the armed forces in this dystopian version is one of the few economic opportunities afforded to minority youth from low-income backgrounds. Renamed PAX, the American army is still busy fighting a variety of wars around the world. Martha soon joins and is shipped to the Amazon Forest, the newest flashpoint of America’s never-ending war on something. PAX forces are fighting to protect the rainforest from cattle ranchers bent on destroying it to make room for more grazing land. The enemy consists of burger chains, and at this point, the dystopia verges on the satirical.

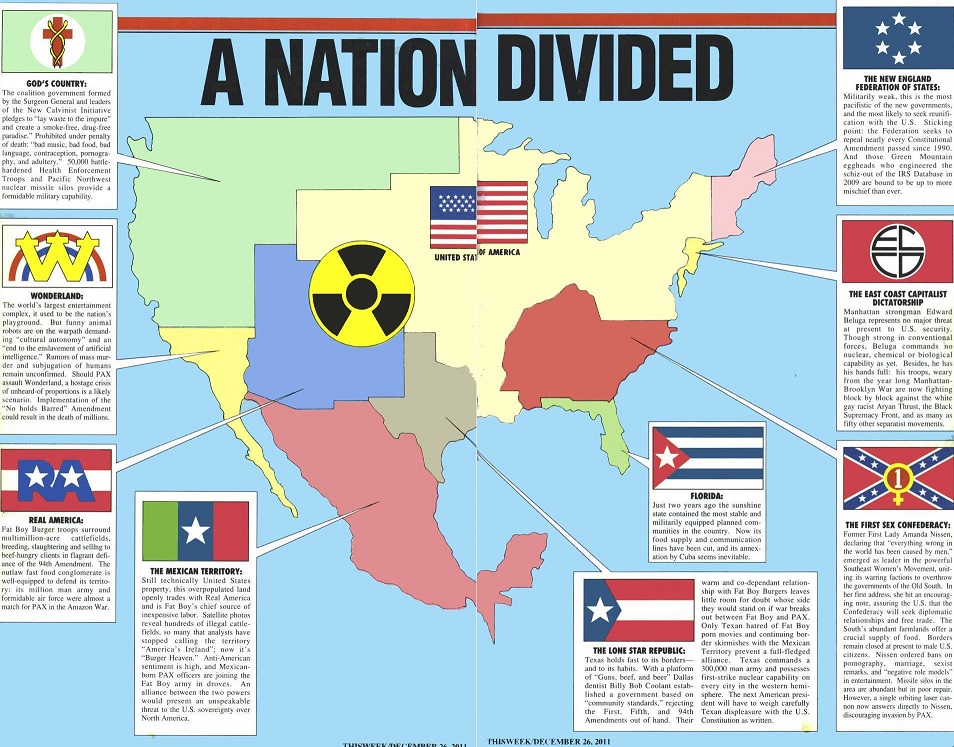

Meanwhile, the USA appears poised to fragment into a thousand different factions amid its growing contradictions. Threats turn to action, and soon America is mired in a Second Civil War, split among such factions as the beef-oriented Texan Republic and an autonomous indigenous territory in the Southwest, a European-style confederacy in New England, an anarcho-capitalist Manhattan at war with Brooklyn, and a biopolitical breakaway region in the Pacific Northwest ruled by a maniacal Surgeon General. Martha proves to be an almost superhuman soldier who plays a pivotal role in the emerging war. Despite this, she stays oppressed by an Italian-America officer who takes credit for her exploits. Nevertheless, Martha always survives whatever abuse is thrown at her. In a bildungsroman of sorts, she persists until maturity gives her enough agency to turn the tables on the world that seeks to nullify her.

Give me liberty is at its most sophisticated when dealing with political and ecological overtones, and surprisingly prophetic too, especially in light of the events of 2020 and early 2021. Miller imagined an ever-chaotic America rapidly spiraling out of control, unlike the managed decline attempted by President Barack Obama and now brought back by his VP. It also serves the usual dose of action scenes and gore for a teenage audience. But for CoFutures, we can dispense with the fighting and stick with the complex subtext of this graphic novel and ask: is this Afrofuturism? Does Give me liberty offer an empowering message, reconstitute the meaning of the past by proposing a better future, or expose the infrastructures of racial oppression? There is a fair amount of exposure in this work, but the result is mildly empowering at best. At one point, Martha and her Native American lover find themselves in an ecotopia of sorts hidden from the dystopian and disintegrating America. Modeled after Ernest Callenbach’s eponymous work from 1975, it ends up serving as yet another backdrop to the internecine clashes driving the narrative. The imaginative universe is subdued by violence as entertainment, resulting in an engaging but philosophically and ethically restrained work. As the story progresses, technology starts breaking down and Miller seems bent on vilifying the unionized workers who keep the imperial gears working. The leap of imagination only goes so far.

After 1998 and despite good sales, the character only returned in less inspired new installments and re-issues. The series’ title is key to understanding it, as it refers to a famous 1775 speech by American revolution leader Patrick Henry (Give me liberty, or give me death!). Martha herself shares the name of George Washington’s wife. At its heart, the series is more about the breakdown of the USA than Afrofuturism, and cannot escape dystopia. The last installment, published in 2007, features the death of Martha Washington in 2095. At the ripe age of 100, she has achieved almost saintly status, but the political situation has deteriorated beyond repair. We never understand precisely what is pursuing the freedom fighters amid the ruins in this decontextualized epilogue to Martha’s epic. In the end, there is only more death.