Notes of the politicization of art: Accelerationism as Futurism

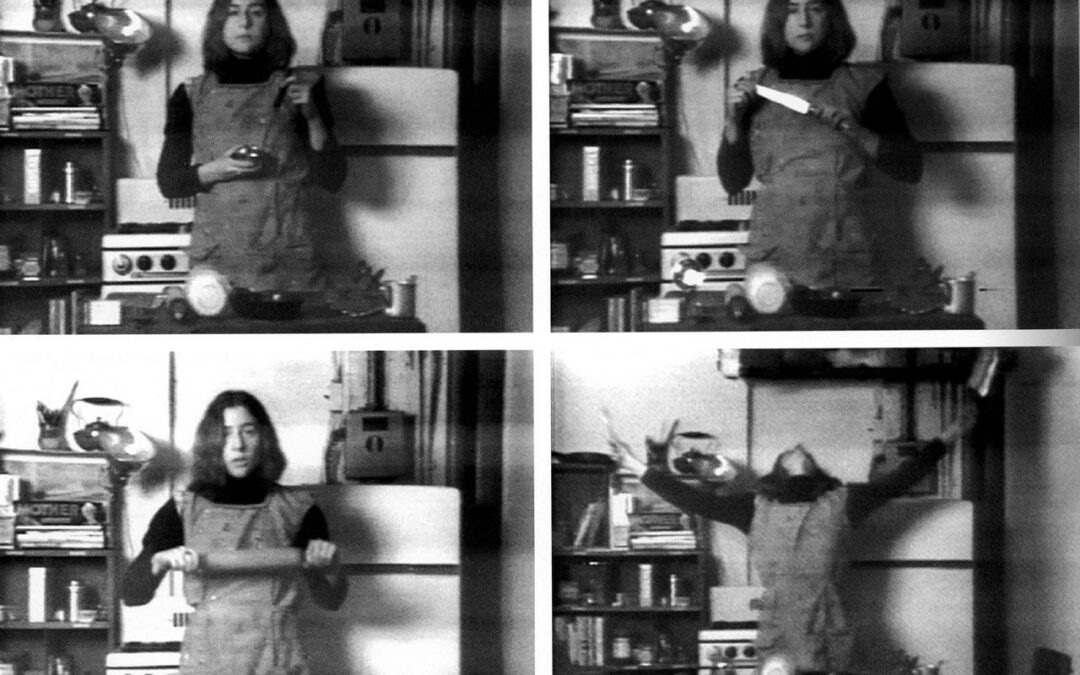

Image: Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen. 1975. MoMA, New York.

In the documentary Hypernormalisation (2016), Adam Curtis raises the issue of art’s depoliticization in the late 1970s. He aregues that artists, or at least the radical ones Curtis was interested in, mostly from the Anglosphere, turned away from collective forms of action and tried to change society from within using their art. It was all related to exhaustion after the hyperpolitical 1960s and early 1970s and the momentous transformations they allowed, including the Civil Rights movement and the Event of 1968. Despite that, the artists felt their efforts were going nowhere. As artists retreated into themselves, Curtis argues, neoliberalism took hold of the political economy and the overall culture created fantasies to be able to deal with an increasingly complex world. Putting it simply: the culture moved faster than the artists.

The result for art was an overall sense of self-satisfaction, as if the act itself was enough, and the old wounds were left to fester. The purulence of the Reagan/Thatcher/Washington consensus years went on and gave birth to a new kind of surveillance capitalism we are now enjoying. Contradictions upon contradictions became too heavy to bear, however. Never something to be relied on, neoliberalism’s moral authority all but collapsed in the space between 2008 and 2020 (global financial crisis, destructive financial austerity, and finally, the rise of neo-fascism in the Western world). But something else seems to have become reinvigorated in the Western world, and it’s politicized art with a temporal and utopian inspiration. It stands in opposition to the notion that the death of utopia had canceled any other future beyond capitalism, as many commercialized apocalyptic and dystopian visions since the 1980s have show, exuding a sense of hopelessness that emerges from neoliberalism. Socially conscious futurisms offer the inverse.

As these notes will show later on, politically-charged artistic practice continued expanding in the margins of the world where the dark utopia of neoliberalism only represented a continuation of everyday dystopia in places long afflicted by the ravages of colonialism and Western imperialism. The current moment in the West, which had been fermenting for some time, at least since 1999’s protests against the WTO meeting, gained momentum following the 2008 financial crisis (Occupy Wall Street, Arab Spring), has put politics again at the center of social speculation. In this sense, the disillusionment in the West offers hope for change.

HBO recently broadcast to acclaim the six-part series White Lotus, about a week of vacation in Hawaii in the lives of White wealthy Americans. In the manner of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s criticism from within (The Great Gatsby), the series shows how privilege can be self-reinforcing and destructive to those around it and how money engenders mechanics of class and hierarchy. It stands as one example of mainstreaming of radical ideas. Redemption lies in radical action (criminal expropriation) and abandoning technology toward a new sociability and nature contemplation (a teenaged son of a wealthy family embraces the traditional ways of Hawaiian natives and discovers the beauty of nature after his electronics are washed out to sea and amid his alienation due to sibling rivalry).

Another example of the the transition from radical art to radical action stands at hear of Mijke de Jong’s Stop Acting Now (2016). A collaboration with Dutch-Flemish artist collective Wunderbaum, the mockumentary depicts the group’s actors finishing their latest politically-charged project with attempts to change the world on a personal level. The actors turn to local efforts, innovative companies and community organizing, all with a strong sense of anticipation for a better future. The devil is in the details, however, and the vicissitudes of human interactions (anger, greed, competition) get in the way of utopian action and show the wide difference between well-intentioned idealism and actualization.

Theatre provides important ways of thinking about politics and aesthetics, as understood from the theorizations of Bertolt Brecht and his v-effekt. Brecht believed that inducing alienation in audiences by repeatedly breaking the illusion of mimesis would help them see the intersections of complex socio-historic trends and personal action. Both v-effekt and the “estrangement” posited by Darko Suvin in his influential explanation of science fictionality derive from Viktor Shklovsky’s theory of ostranenie (“making it strange,” or defamiliarization). Estrangement is both the deferred meaning crucial to creation nudging the audience to see the world in new ways. In the 1960s and 1970s, Augusto Boal in Brazil took the Brechtian proposition one step further with the Theatre of the Oppressed, directly engaging art practice in emancipatory action to turn spectators into “spect-actors.” He sought to raise awareness of the political by making audiences “know the body” — both the individual and collective one; making the body expressive and, crucially for contemporary futurism movements, using the theatre as both language and discourse.

Considering how art can create positive feedback loops with cultural movements, the role of science fiction in this emergent culture (in the manner identified by Raymond Williams when differentiating structures of feeling) is one of “fictioning” as a speculative blank space while the communities of readers and writers, the mass cultural genre side of science fiction, becomes a social technology when repurposed for activist ends. Undoubtedly, social activists had long been developing networked forms of intelligence while working toward emancipation goals. These networks seem to be blending into the science-fictional ones, albeit not without significant collective effort, as the travails of puppygate show.

How can we reverse engineer these processes to better understand them? Breaking down the linearity between Futurism in the early 20th century and today’s Accelerationist movement is one way. Futurism called for the glorification of technology and velocity before the First World War and had a considerable impact worldwide. Futurism became eponymous with a sense of modernity and novelty, as well as the instrumentalization of technology in culture and politics. Russian artists embraced it during the Soviet Revolution until political realities deemed them too disturbing to the rising new order. In Latin America, José Carlos Mariátegui (Peru, 1894-1930) was heavily influenced by Italian Futurism and Antonio Gramsci when he sought to apply Indigenous communities to a new form of progress. In Brazil and Argentina, it inspired nationalistic artistic movements that problematized Latin America’s search for differentiation from Europe and for forging a native culture from transculturality. Italian Futurism later devolved into an ancillary arm of fascism, losing its impulse amid the more negative aspects of its genesis, mainly the cult of violence and a deeply misogynistic nature.

Accelerationism, for its part, emerged from the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) that formed at the University of Warwick in the 1990s. Soaked in the triumphant moment of Western capitalism following the Soviet Union’s collapse, it also glorified technology and modernity, seeking to embrace it in combination with an infections jouissance that was equal parts satire of academic self-importance and serious innovative theorization. Among its concepts was hyperstition, or the notion of ideas that impose themselves into the culture and shape it, operating within a scrambled temporality in which imaginations of the future influence the present. Akin to the idea of meme coined by Richard Dawkins (not unlike today’s memes of internet culture but grounded on evolutionary theory), hyperstition is best exemplified by art practices that use techniques of speculative fiction. Fictioning of myth-science, as Goldsmiths College’s Simon O’Sullivan puts it, seems to be in full swing these days with the global spread of Afrofuturism and the growing clout of Indigenous Futurism in visual arts, literature, and fashion.

Like Italian Futurism before it, these movements emerge through manifestoes and acts of self-assertion. Thus, for example, one might announce the creation of a particular type of Futurism or seek to identify them. Of course, all of this is valid in the game, and these intervention techniques are akin to those employed by SF to define its boundaries. But if futurist actions are boundary objects of their existence, then what makes such fictioning practices real? I therefore argue that a critical mass of participants and cultural importance is what makes these futurisms real. As much as one would like to intervene in culture, and they are certainly free to do so, a simple action can be a part but not the endgame of any futurism. If there are not many people adopting the hyperstitional notion posited by a futurism, it only retains a spectral existence. Still, if adopted by a sufficiently large number of people, it enacts fiction into reality through collaborative practice.

Also like its Italian ancestor before it, Accelerationism embodies the old idea of technology as pharmakon. Technology can liberate or oppress; humankind’s relationship with technics is both creative and destructive; moreover, members of the same fertile movement that emerged from the CCRU lately turned to reactionary right-wing politics, all in the desire to enact enough of an acceleration that would destroy capitalism. Conversely, Brazilian Afrofuturists and Canadian Indigenous futurists have reached enough critical mass that their effect on the cultural imagination to enact a kind of change that defies co-optation and represents more than just destruction or surrender to technology. For the first time, neoliberalism may have found an opponent that does not let itself be assimilated but instead assimilates and changes the very essence of that which wants to domesticate its power, in the same way that it turns Western science and technology on itself.

Yuk Hui’s proposal of technodiversity might offer a way out of this duality, but its density and broad arch require a deeper discussion. In essence, Hui’s project is to transcend the dominant cosmotechnic of capitalism and Western technology. Through the emergence of non-Eurocentric forms of doing things, to put it simply, we may escape the cancelation of the future. By forcefully occupying spaces previously denied, the actual futurisms described above represent one step forward.

References

Hypernomalisation (2016) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thLgkQBFTPw&ab_channel=SamJohnson

Pieter Lemmens (2020) Cosmotechnics and the ontological turn in the age of the Anthropocene, Angelaki, 25:4, 3-8, DOI: 10.1080/0969725X.2020.1790830

Simon O’Sullivan (2017) “Accelerationism, Hyperstition, and Myth-Science.” Cyclops Journal. 2: 11-44.