Fairytale’s end

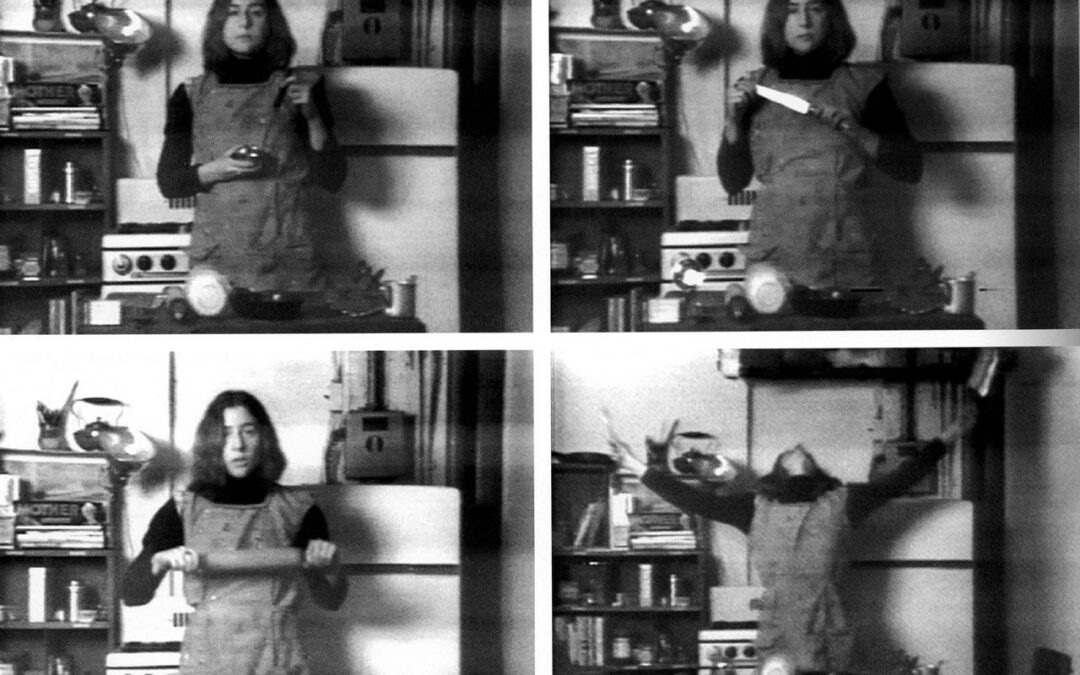

The last oil-workers to leave norwegian rigs after the great “scrubbing”. Photo: Tomoya Flesvig, from Snipp Snapp Snute exhibition at Norwegian Cultural History Museum (2067).

An unresolved nostalgia haunts new exhibition remembering the end of oil and gas-excavation in Norway.

“We wanted to mark that an era in Norwegian history is over. There has been so much focus on the future that we have forgotten to look back and say, well, that was that,”(Dagbladet, 03. august, 2067). This is what the creators themselves say about the new exhibition “Snipp Snapp snute“, an exhibition that has brought debate-forums in most of this country’s newspapers to boiling-point.

The task of holding “repast for the oil age” has at least been taken seriously by the creators. In the well-filled rooms of the new “flourbag”-building NOCH (Norwegian Cultural History Museum, drawn by architectural firm Bernhard the dealer AS) you are sucked into nostalgia. But it is a nostalgia that lacks warmth, a troubled nostalgia. It’s like stepping into the shelf above the fireplace for a few hours, but also remembering a grandfather you had a difficult relationship with.

Photographer Tomoya Flesvig is responsible for most of the content, together with celebrity-anthropologist Siri Hylland Spjeldnæs Herbjørnsrud. The photography is in black and white and sepia colors, timeless markers for “olden days”. Some show offshore activity, but most are from recent times around the winding up of oil activity on Norwegian oil-fields. The place of honor has been given to a photograph that has become iconic (which has also been printed in Morgenbladet). It shows a group of Norwegian oil-workers with their backs to the camera (as well as the back of the former Minister of Petroleum and Energy if you look closely). They are waving at a helicopter that has just taken off. From the helicopter, a fat man in mink fur with dark brown hair and Rayban glasses waves back. This is Eric Barnard, CEO of Neptune Energy. As is well known, he was the last representative of a multinational oil-giant to leave Norway, in a symbolic ceremony after the great so-called “scrubbing” of the Norwegian Sea.

It was all in order to secure norwegian futures. It was for the kids, it was all for them!

– Former offshore engineer Karl Heggerud.

Snipp, Snapp, Snute succeeds where many a historical exhibition fails; it avoids being dull, even for its youngest patrons. This is partly thanks to the different types of objects on display. Tomoya Flesvig has obtained an old “Equinor” sign, and the artwork of Henrik Olai Kaarstein “Gas-infused rag in dripping pot of oil on stove” has been loaned to the exhibition from Gether Contemporary in Copenhagen.

The most striking thing about the exhibition, however, is the voice-recordings, which can be heard through real plastic headphones. These are part of Siri H.S. Herbjørnsrud’s doctoral project. Some of the selected sound clips are heartbreaking, there was not a dry eye at the front door of NOCH, at least among us who remembered the intensity of the time of the great scrubbing. “Families were divided,” says former Offshore engineer Karl Heggerud through the earphones; “The worst thing was probably that my children were so livid at me. You shit on the future, they said. And then I got angry too, I’m still not talking to one of my sons. All the work on the rig, the learning, the technology development… it was all in order to to secure Norwegian futures. It was for kids. It was for them, all for them!”.

Approximately 200,000 Norwegians were employed, directly or indirectly in the petroleum industry in 2019. It took only ten short years from Norway stopping to search for oil in 2031, to the great scrubbing of the Norwegian Sea. Meanwhile, we witnessed the total reorganization of former Equinor to what we today know as Grønn Kraft, as well as explosive growth of the offshore wind-industry. My granddaughter can not even imagine painting a sea landscape without the mills. When she was very little she thought they were part of the sea, I remember. Now she is with me at this exhibition and I try to tell that when I was young, the oil-industry was the most important in Norway, that it was completely normal to work in that industry. That there were no mills. She responds with the word young people say about everything and nothing nowadays: “Grandma, Rakasha!”. She simply does not believe me.

Former offshore safety inspector Eva-ann Knutsen: “Everyone put on their “climate glasses”, and then we became the bad guys. It hit me hard, even though I was offered a new job. I considered signing up for NV [Guardians of the Nation]. Fortunately, I did not, but the bitterness lasted a long time,”.

Focusing on the social and psychological consequences of the end of the Norwegian “oil-fairytale” is what sets this exhibition apart from the rest. Few have dared to broach the topic. “We have moved on, and there is no point in dwelling on the past,”. These are the words of Minister for Development Sol Hulda Fredheim: “The consequences of dwelling on the past have been shown by the inhuman actions of the organization that calls itself Guardians of the Nation. The green shift had to take place. It was necessary to get it done quickly, most upright people understand that now,”.

What was good for the future in the past may not be good for the future in the present

Former offshore safety-inspector Eva-Ann Knutsen

Had there been a parliamentary election tomorrow, the red-greens would not have won the majority, the latest super-poll has shown. This is due to a sharp decline in the popularity of Fredheim’s party, GFN (Green Future for Norway, formerly Extinction Rebellion Norway). This exhibition is a timely reminder that the rapid green transition is yet to be processed and reconciled in society at large. “It took me a long time to grasp it, and I’m not alone in that,” Eva-ann Knutsen continues through real plastic headphones: “I have been hiking a lot, around the Bleikvassli mine, it is right next to where we live. I walk and think. I especially think about coalworkers and the miners of olden day, the people who worked in places like that. We kind of have something in common now. But I have moved on. There is something about understanding that what was good for the future in the past, may not be good for the future in the present,”.

Snipp, Snapp, Snute will remain in NOCH for a year, until September 13, 2068.

*First published in Klassekampen saturday 18th september 2021, all rights reserved.